Continuing on from recent articles discussing how the indigenous Mentawai community deals with illness and loss of life, I’d like to delve a little deeper into the practices of traditional Mentawai medicine; those who are trained to administer it; and the impacts caused by an increased lack of community access to it.

Firstly, it‘s worth mentioning that traditional medicine has been developed and depended upon by the Mentawai for thousands of years. It wasn’t until as recent as 1901 that the first missionary (August Lett) arrived; and 1954 before introduction of the nationalized programs designed to ‘integrate the tribal groups into the social and cultural mainstream of the country’ – shortly after Mentawai became a part of the Indonesian State (1950).

The origins of Mentawai medicine in fact date back to the arrival of the very first Sikerei. Which, perhaps reflective of the wisdom and foresight of their forefathers, is said to have come in the way of a young child named Simaliggai. As ancient mythology goes, Simaliggai possessed an intimate connection to the forest – the child knew how to hunt, gather, grow, heal, preserve and maintain peace within. Naturally, everyone wanted to know how to did this.

Simaliggai, taking advantage of this fortune, decided to teach this knowledge to others and, in doing so, formulated a way of being called ‘Kerei’. Whereby, following in Simaliggai’s footsteps, everybody who learnt these Kerei skills would also become educators – devoting their life to teaching, healing and protecting others. Which, given this quickly became the most aspired role in traditional Mentawai society, does offer some insight into the origins of cultural values and success in sustaining their existence.

In essence Sikerei are the backbone of Mentawai culture and sustainability – the societal figure the entire community turned to for healing, guidance, comfort, reassurance, protection and safety. Providing medical services is certainly one element but it’s fair to say that it goes a lot deeper. To give context, I thought I’d share with you an interesting excerpt on Community Health from the indigenous Mentawai Community Research Report document:

Access to health care on Siberut Island has not altered since 1998 when Cheeseman and Kramer conducted the health research study ‘Incidence of Illness Among the Mentawai People of Siberut Island’, as their description of the island’s modern health care facilities remains valid: ‘Currently there’s only one (operational) government-run community health clinic (puskesmas) in each of the two district towns, Muara Siberut and Muara Sikabaluan. A Puskesmas has been built in each of the PKMT villages (over 60 settlements) throughout the island but, with medical staff concentrated solely to the two district towns, none of these have really ever been operational’.

Meaning that, for all residents of communities located in the interior or on the west coast of Siberut – whom due to financial restrictions are seldom able to afford the cost of transportation to these district towns – they are effectively unable to access these modern health care services.

In spite of this, findings show that the general level of health within the Matotonan community remains high, as not one person canvassed during the baseline survey cited health or access to medical assistance as being an issue or barrier to their existence here.

A possible reason for this finding could be attributed to the presence of Sikerei. Whose role, as confirmed through qualitative data by 80.6% of all other demographics, is ‘to treat, heal, and protect the people’. This meaning that, if Sikerei are fulfilling the role as a community doctor, then the Matotonan settlement – where there’s found to be around 1 Sikerei per 35 residents – actually possesses Siberut’s highest ratio of doctors per capita.

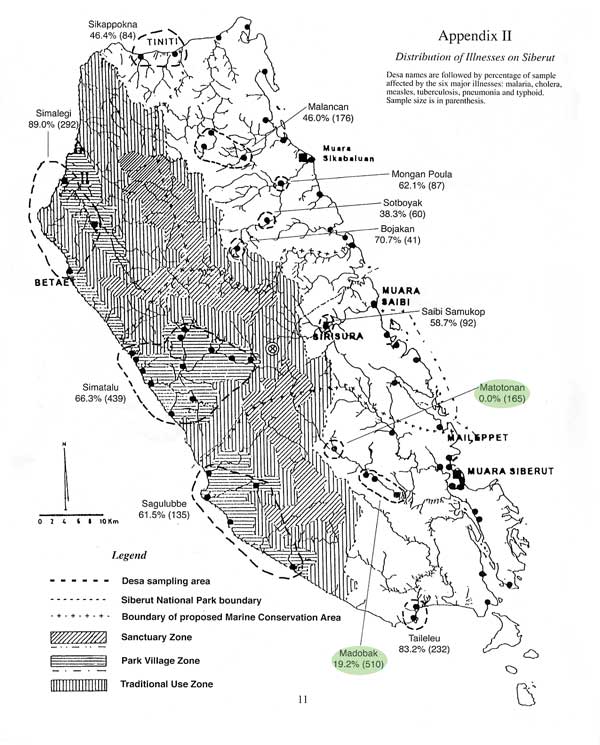

Adding weight to this is the data gathered by Cheeseman and Kramer during their aforementioned health report, which sought statistics on the proliferation of six major illnesses found on Siberut Island – malaria, cholera, measles, tuberculosis, pneumonia and typhoid.

As seen in figure 1.3 below, when focusing on the region where almost all the last remaining Sikerei actively practicing traditional Arat Sabulungan culture are located, of the 165 people canvassed by the pair in Matotonan there were no apparent cases of illness. Whilst in Madobak, the only other village surveyed for the report within this particular region, a mere 19.2% (of 510 people) reported having been affected.

When comparing this against all other settlements throughout Siberut these figures are considerably low. Which, coupled with findings showing 98.6% of the community would prefer to use traditional medicine administered by Kerei if they were to become ill; and that 77.1% believe that the community would not survive without medical attention provided by Sikerei, strongly suggests that the presence of an adequate number of trained Sikerei continues to have a significant impact on disease control and overall community health and wellbeing.

This is not meaning to take away from the benefits of modern health services here. Not at all. We know, with reference to the previous article, that these do save lives. I’m sure Aman Masit Dere and his extended family’s eyes are far more open to it as a secondary solution now too. But the reality is that this option – for many – is just not feasible. So my view, based on these findings, is that supporting the preservation and practice of indigenous healing as an alternative does deserve serious consideration here, as oppose to suppression.

Interestingly, listed in the Government’s ‘Plans for Improved Health Care on Siberut’ (1995-2000)(PHPA 1995 p.200) was an objective to ‘Establish a local connection through dialogue and training with Kerei’. Which, in detail, stated plans for the ‘establishment of dialogue between modern health care workers and traditional medicine men (shaman/kerei) with regard to frequent diseases, their treatment and prevention, and upgrading effectiveness of Kerei in basic first aid; particularly in areas not frequented by mobile policlinics’. Unfortunately this objective was never pursued.

It’s not much (compared to tradition) but, with Sikerei permission, I’ve begun documenting certain aspects of their traditional medicine on account that one day future generations of Mentawai may once again reestablish connection to its significance and relevance to their long-term health and wellbeing.

During the forage for medicine shown in the photographs throughout the article, which was required for severe stomach pains, Aman Alangi gathered the following plants (Mentawai dialect): Sipeupeu, Palugarejat, Simuinek, Laipet, Sarasarak, Sipukole, Pelekak, Simakkainauk, Gozo, Sipukairabik, Alutuet, Pasisikuk, Tarasilalu, Pasisingin, Simamait, Muttei, Pugetta, and Pukatutup.

Thanks for reading.

4 Komentar